Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Industrial policy discussions often focus predominantly on the manufacturing sector, neglecting the fact that services account for a significantly larger share of GDP in nearly all countries. Furthermore, trade in services has been growing at a pace that outstrips that of goods trade. Despite this reality, there exists a notable gap in the understanding of the selective policy interventions that are applied within service sectors.

To bridge this gap, we utilize the World Trade Organization’s Trade in Services by Mode of Supply (TISMOS) dataset, aligning it with data on selective policy interventions from the Global Trade Alert (GTA) that pertain to the services sector. This approach illuminates the role of selective corporate subsidy interventions and their potential connections to service sector exports.

Services Trade Dynamics: Stylized Facts from the TISMOS Database

The TISMOS dataset categorizes trade in services into four distinct modes of supply:

- Cross-border supply: Services are delivered from one country to another without the movement of the consumer or producer, such as a UK university offering online courses to a student in India.

- Consumption abroad: Services are provided within a country to consumers from another nation, including tourists accessing services like museums or medical care in the host country.

- Commercial presence: Services are offered by businesses establishing a presence in another country, exemplified by a British bank opening a branch in India.

- Presence of natural persons: Services are rendered by individuals from one country temporarily in another, such as a consultant traveling to provide services to a client.

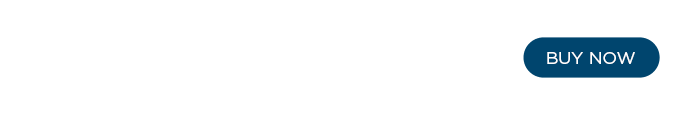

While commercial presence remains the leading form of service exports, a shift has occurred since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, favoring cross-border supply. This transition indicates a potential decline in in-person service delivery as exchanges that do not necessitate physical presence gain popularity. However, the percentage change from 2017 to 2022 shows an upward trend in both commercial presence and cross-border supply.

The observed decline in the global share of commercial presence can largely be attributed to a more substantial percentage increase in other categories. The ongoing establishment of local affiliates by foreign suppliers underscores the continued importance of close contact throughout various service delivery stages, including production, distribution, and after-sales support. Additionally, there appears to be considerable growth potential in sectors such as tourism, which may experience a recovery in services provided to consumers from other countries.

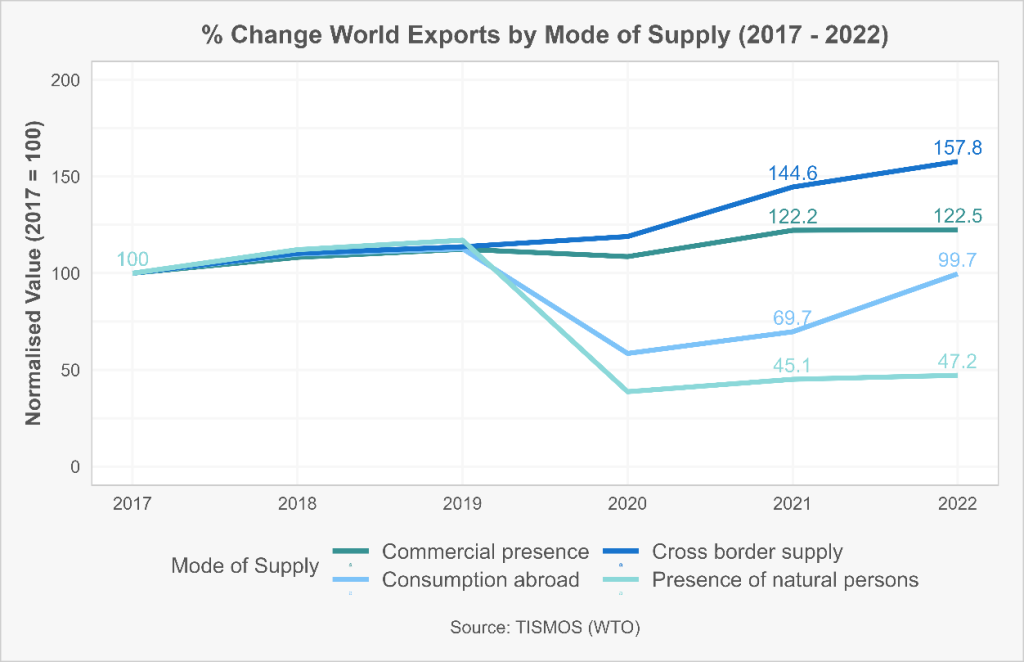

The TISMOS database offers insights into services trade broken down by major exporters. Notably, over 50% of global service exports originate from the EU and the USA combined, with China accounting for only 8.2% of total world service exports in 2022. This concentration within the services sector carries significant implications, as trade partners may be compelled to align with US and EU regulations to engage in service exports, thereby granting these regions substantial leverage over global trade standards.

Emerging markets possess strategic opportunities for expansion in areas linked to digital transformation and remote services, which can bolster economic diversification initiatives. For instance, China has seen a remarkable growth rate of 126% in cross-border supply service exports post-2020, while the EU-27 recorded a 57.8% increase. However, despite these figures, China’s global export share in 2022 remained below 10%.

When examining services necessitating a commercial presence, we observe a notable increase in Chinese exports, despite a decline in 2022 compared to the previous year. In contrast, the United States maintained its upward trajectory, while the EU fell behind the global average. This trend highlights the resilience of US multinational service firms, which continue to expand by establishing subsidiaries or acquiring foreign companies. For example, IBM has set up numerous R&D centers globally to cater to regional markets, while Microsoft has established data centers worldwide to ensure compliance with local data regulations.

Conversely, challenges such as geopolitical tensions and trade barriers could present obstacles to Chinese firms seeking expansion through foreign direct investment (FDI). Recent instances of trade restrictions, such as tariffs and the banning of Chinese telecom equipment, may prompt these firms to establish operations abroad to circumvent these barriers. For example, Türkiye has implemented higher tariffs on imported electric vehicles while simultaneously incentivizing foreign manufacturers like BYD and NIO to set up production facilities within the country.

A Deeper Dive into Selective Subsidy Interventions Shaping Service Sectors

The GTA database provides a robust framework for analyzing selective subsidy interventions that favor service sector firms. Notably, consumer subsidies without nationality-based discrimination are excluded from this analysis, allowing us to focus on subsidies directed toward service producers.

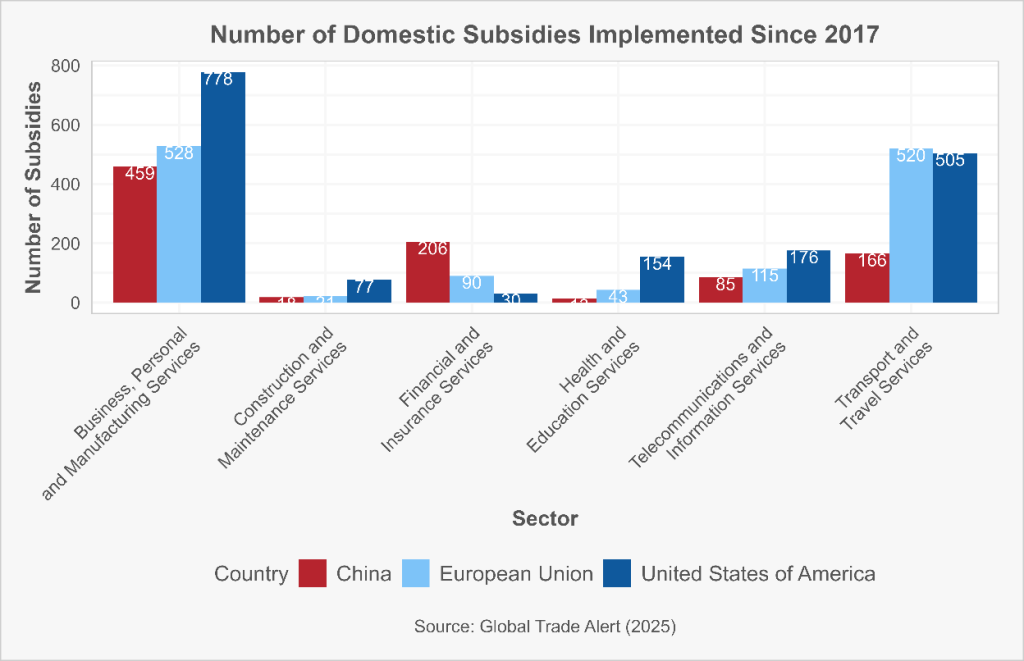

Since 2017, the majority of corporate subsidies awarded by China, the EU, and the US have benefited producers in the Business, Personal, and Manufacturing Services sector. The US typically grants the most subsidies to companies in this sector, while the EU focuses on transport and travel services, and China leads in financial and insurance services subsidies.

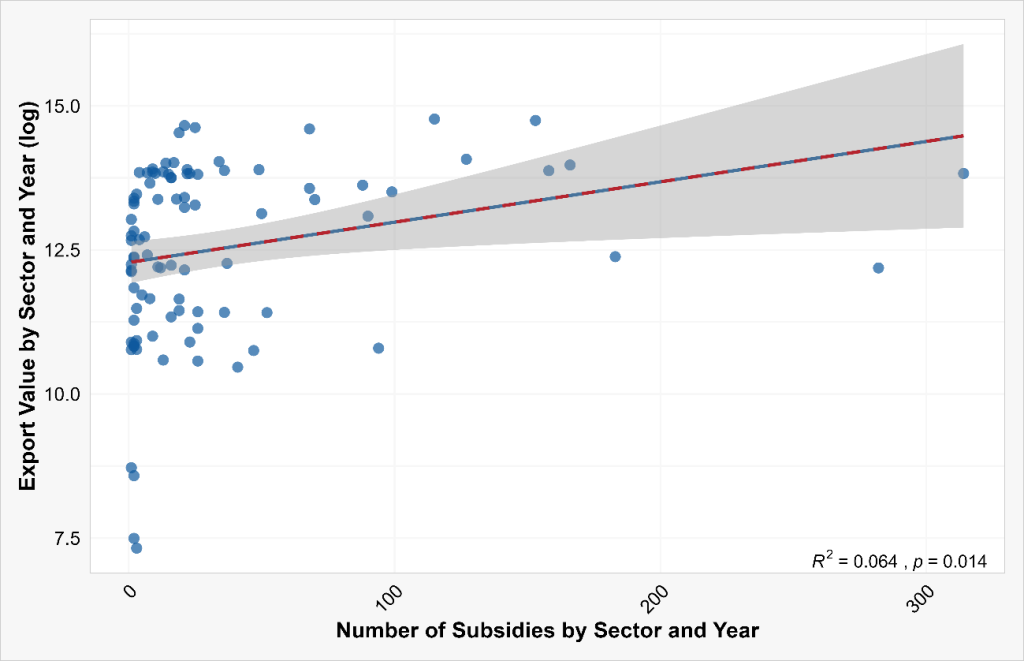

Our analysis indicates a positive correlation between a country’s sectoral exports and the number of subsidies awarded annually, with a correlation coefficient of 0.4. This suggests that countries tend to subsidize sectors where they have demonstrated export strengths, reinforcing the idea that subsidies are strategically employed to bolster services with a comparative advantage.

Enhancing transparency is vital for comprehending trends and dynamics in service trade. The WTO’s TISMOS initiative, which integrates information on modes of supply, sectors, and trade flows, marks a significant advancement. Coupled with the GTA database, which tracks industrial policies affecting the service sector, there is substantial potential for learning when these data sources are combined.

Our findings suggest that service providers in different countries display preferences for specific modes of supply. The United States, for instance, continues to emphasize commercial presence, capitalizing on the strength of its multinational service firms. In contrast, China increasingly concentrates on cross-border supply, propelled by its advancements in digital services, including software development and cloud computing.

As we look toward 2025, the trends identified between 2019 and 2022—most notably the shift toward cross-border service supply and the growing prominence of China in digital services—are likely to persist. Rising geopolitical tensions and new trade barriers may drive countries like China to expand their commercial presence in foreign markets, adapting to the evolving regulatory landscape. Meanwhile, the EU and the US are expected to continue focusing on subsidizing key service sectors, leveraging selective policies to maintain their competitive edge in the global service trade.