Lameness is likely not secondary to systemic illness with common pathogens

Editor’s note: The following is from a poster presentation by David Buckwalter and faculty advisers, University of Pennsylvania, during the 2024 annual conference of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians.

Lameness represents a widespread issue which affects viability and growth, ultimately impeding efficient production and adding extra costs to producers. The causes of lameness in growing swine, however, are poorly elucidated and often difficult to diagnose in the field. The objective of this study was to use gross pathological examination to compare lesions in lame and non-lame growing pigs to better understand the etiology of lameness in growing pigs.

Two production companies enrolled 5 farms each for a total of 10 farms. On each farm 2 pigs were chosen, a single lame pig (L) and a single non-lame control pig (C). Pigs were identified as lame if two observers agreed that the animal was slow to rise, limping, reluctant to walk or reluctant to place weight on one or more limbs. Pigs were euthanized and transported to a diagnostic lab for complete postmortem evaluation. Visceral examination was competed on all pigs, all four legs were excised, and each joint examined grossly. Joints were scored for the presence or absence of synovial hypertrophy, hyperemia, or effusion as well as for lesions consistent with osteochondrosis (OC) and physeal bone lesions.

One joint in each L pig that contained synovial lesions was swabbed and a swab was taken from the same location on the C pig from that farm. Odds ratios were calculated for the odds of OC lesions, visceral lesions, and having multiple types of lesions in the lame versus non-lame pigs using a Fisher’s Exact test.

Lameness lesions

The average farm size was 3,624 pigs and the mean age of the pigs was 14.6 weeks. Eight females and 12 males were selected. Eight sow flows were included with five being comingled. There were 16 times greater odds of having multiple lesions in the L pigs compared to the C pigs. The odds of having an OC lesion were no different between the L and C pigs. There was no difference in the odds of having a visceral lesion in the L pigs versus the C pigs.

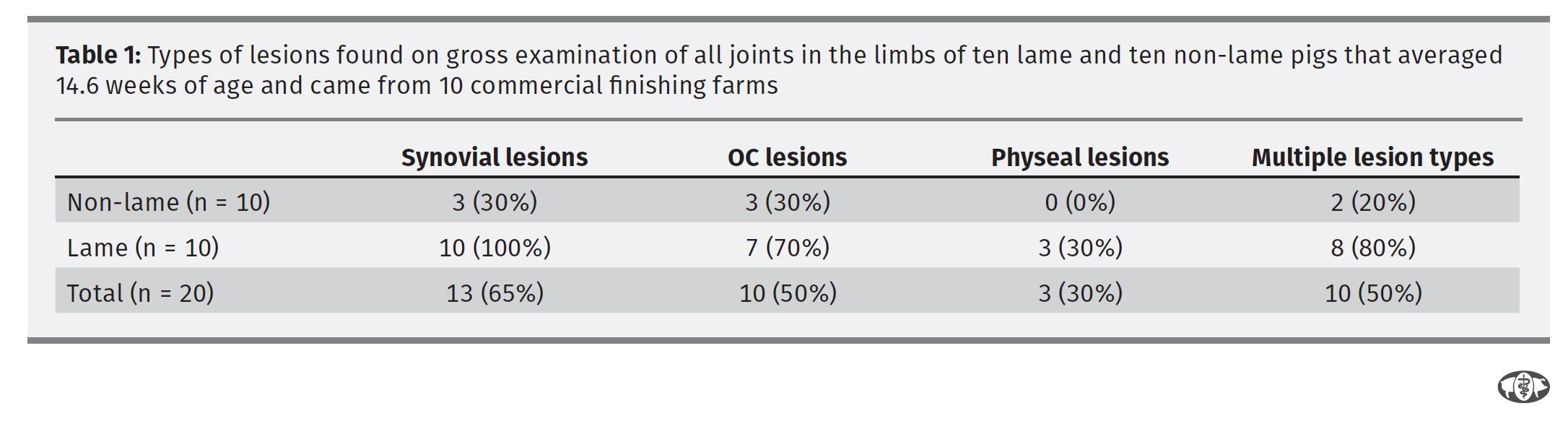

All 10 of the L pigs had at least one synovial lesion while only 30% of the C pigs had synovial lesions. None of the C pigs had physeal bone lesions, whereas 30% of the L pigs had such lesions. (No odds ratios could be calculated for either of these lesions).

There was a significant difference in the median numbers of locations where there were lesions in the L pigs compared to the C pigs (P<.001) (Table 1). Lesions were evenly distributed between front and hind limbs with 16% of locations scored in the front limbs having a lesion and 14% of the locations in the hind limbs. Only one L pig joint was found to be positive for M. hyosynoviae and none of the C pigs tested positive.

L pigs had more lesions and were more likely to have synovial lesions than C pigs. Only one pig was found positive for M. hyosynoviae, so the cause of the lesion is unclear. In contrast to other studies of pigs this age, the osteochondrosis lesions found were mild and not more likely to be found in the L pigs, decreasing the likelihood of its involvement in the clinical lameness.

Systemic disease was not more prominent in the L pigs, indicating that lameness is likely not secondary to systemic illness with common swine pathogens such as Streptococcus suis, especially given that none of the pigs had overt septic lesions (fibrinosuppurative joint or bone lesions).

Determining the cause of lameness in these animals remains challenging, though bacterial pathogens that cause lesions to the synovium like M. hyosynoviae may be more likely than other causes based on these findings.